“I had to go without fags for four days last week. What agony, eh? Well Charlie, my son, I could write you heaps but my office isn’t that good, what with my desk being a bundle of straw.”

Private Joseph Goldsmith was dead just days after writing this letter on November 14, 1918. He lived to see Armistice Day but succumbed to the Spanish Flu while recovering from being shot in the Battle of the Somme.

He was just 21 and had spent two years fighting for a future he never got to live.

Letters to his big brother Charles – poignant and funny but rarely tinged with the sorrow you would expect – reveal the gloomy reality of the First World War.

For his nephew, John Goldsmith, they are an important part of his family history.

He is too young to have ever known his uncle but having inherited the letters he sent to his big brother Charles, he is determined to keep his legacy alive.

John, who now lives in St Mary’s Avenue, Wanstead, said: “My dad mourned his youngest brother all his life. He never forgot him.”

Through the letters, which paint a solemn picture of life during the Great War, he has been able to piece together bits of his personality.

Joseph was drafted off to war aged 19. His oldest brother was exempt because he worked for the family business, moving materials to the docks to go to France – something considered a vital part of the war effort. Middle brother Bill joined the Royal Flying Corps.

"I’m really sore…they do make you work," he recounts in one letter, from a training base on the Isle of Sheppey.

His letters are full of hope at times, as he dreams of the promise of a brighter future.

"Jerry (slang for the Germans) has been over dropping his peace pamphlets. I can see it being over by Christmas, yet, what do you think?"

He affectionately refers to his brother as ‘old sport’ and ‘my son’ as he signs the letter off with a chipper ‘aurevoir.’ In another letter, he refers to his commanding officer as ‘hot stuff’ and ‘a bit of a blighter’.

He tells Charlie, or ‘Chuck’, how he dreams of joining the flying squad and still plans to try, even though he knows he hasn’t got the right experience.

"There’s one thing damn rotten about this lot" – his letters continues - "and that is we are not given any leave whatsoever. Out to France without it.

"To cut things short, you work, or rather drill for 24 hours, and the rest of the day is your own."

He signs his letters off with a bright ‘Your loving brother, Jos’.

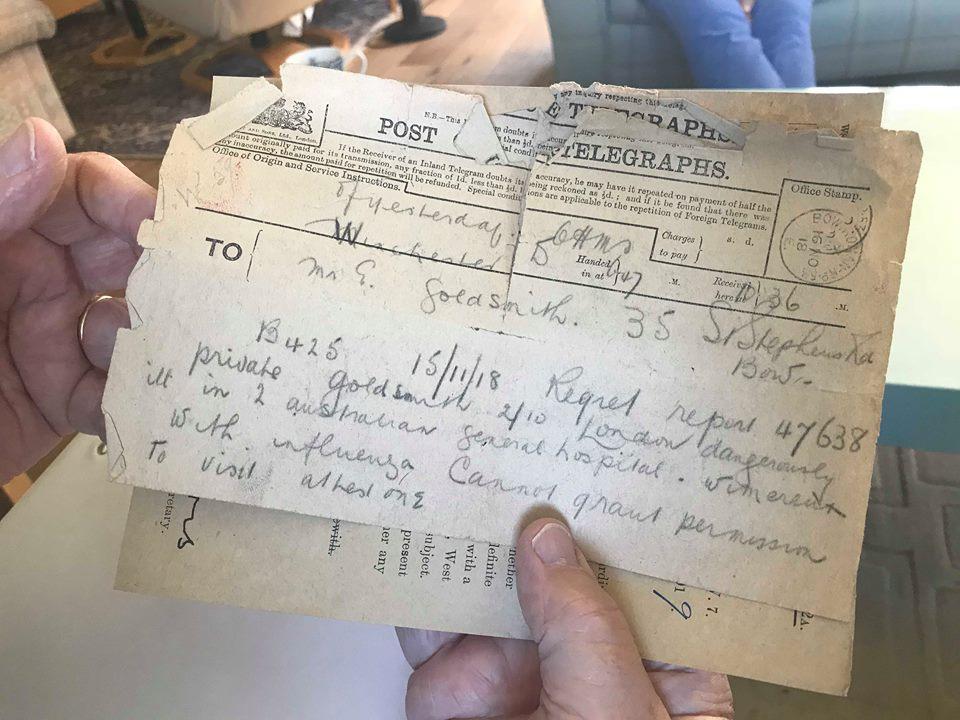

The way Charles was told of his brother’s death would seem heartless by todays’ standards. He knew Joseph was dangerously ill with influenza, but nothing could have prepared him for the next telegram.

It simply said: ‘Private J Goldsmith died in the Australian General Hospital in Wimereux from influenza’ Charles was told of his death in what by today’s standards, would seem heartless.

But what happened next is a cherished family story.

He is buried at the Terlincthun Military Cemetery and in 1922, some years after the end of the First World War, the King and Queen, George V and Mary, were given a tour.

They were accompanied by literary Nobel Prize winner Rudyard Kipling, who was mourning his son, Jack, who was killed in the Somme.

On passing Joseph’s grave, Kipling happened to notice the epitaph Charles had so lovingly composed.

A real good fellow. God bless him.

Kipling remarked: ‘How splendid is this?’

The brief exchange was deemed worthy enough for a front-page mention on the Daily Express.

Mr Goldsmith still has a copy of the newspaper, yellowing and slightly creased, but a beautiful tribute to the uncle he never got the chance to meet.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel